West Virginia Family Treatment Courts

Family treatment courts assist parents working to overcome substance abuse disorders and reunify families when children are removed due to parental substance abuse. This Science and Technology Note explores how family treatment courts operate, their impact on West Virginians, and possible funding sources to support programming.

Research Highlights

Parental substance abuse is cited in 44% of West Virginia’s child removals.

The Legislature made family treatment courts a permanent program in 2021 after a successful pilot program in 2019.

West Virginia’s family treatment courts have reported over 1,000 parent participants and a 55% graduation rate.

Family treatment courts in West Virginia are funded by grants, similar to Pennsylvania. Both Ohio and Tennessee’s legislatures allocate funds to support family treatment courts, reducing reliance on external grants.

What Are Family Treatment Courts?

West Virginia reports that 17 out of every 1,000 children are in foster care, which is higher than all neighboring states. There are many reasons for child removal, though parental substance (alcohol or drug) use is cited as a cause in 44% of all cases and abuse or neglect are cited in 62% of cases. The foster care system was recently identified as a major priority for the West Virginia Legislature and Governor Morrisey, with approaches including early interventions to prevent foster care referrals. Family treatment courts (FTCs) are one such intervention implemented in West Virginia.

FTCs are specialized courts whose mission is to help parents access treatment for substance abuse disorders and establish a permanency plan for children that are removed due to abuse or neglect. FTCs are operated at select circuit courts and overseen by the Supreme Court of Appeals. Parental participation is voluntary, and parents are eligible if they have been judged by a court to be an abusing or neglecting parent, have been granted an improvement period, and have a substance use disorder [1]. If a parent chooses to participate in a FTC, there is a collaborative effort between the circuit court, child protective services, and substance use disorder treatment centers. The FTC ensures that the parents are receiving treatment, provides case management support, and requires frequent drug testing. Parents are also afforded time with their children and help navigating their court appearances, with everyone working toward a goal of recovery and permanent reunification.

West Virginia Family Treatment Courts

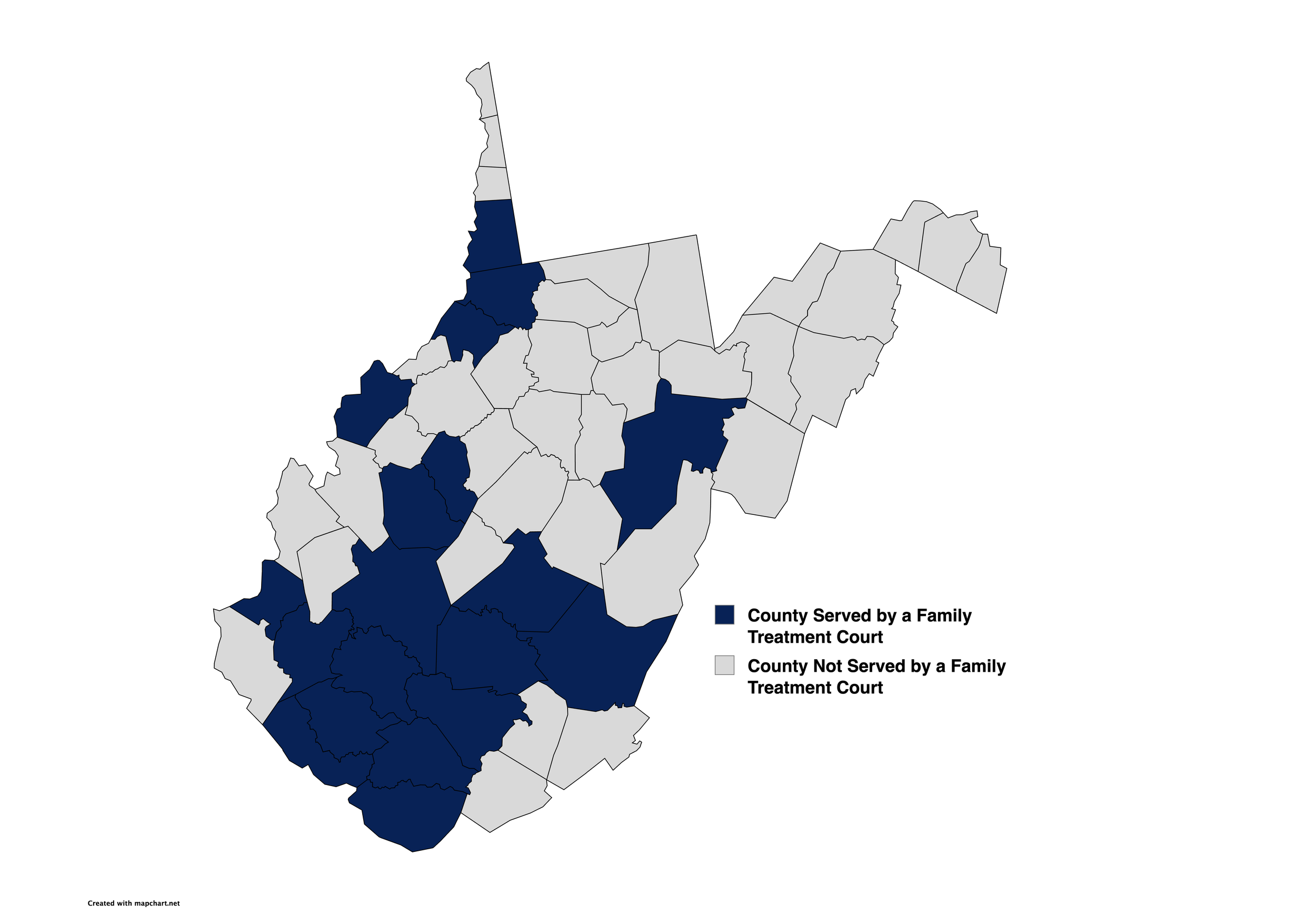

West Virginia implemented a FTC pilot program in 2019 (HB 3057), allowing the Supreme Court of Appeals to initiate them in up to four counties. FTCs were implemented in Randolph, Boone, and Ohio counties to determine feasibility, acceptance, and success. In 2021, the Legislature designated FTCs as a permanent program (HB 2918), and there are currently 13 FTCs serving 19 counties in West Virginia [1].

Based on Testimony from the Treatment Court Presentation at the January 2026 Legislative Interim Session.

FTCs have impacted over 1,000 parents and children in West Virginia. Since 2019, 1,070 parents have been referred to FTC services, and they have a 74% acceptance rate and 55% graduation rate [1]. Courts have reported that 93% of parents being assisted by FTCs test negative for drugs in mandated random drug screenings throughout the program [1]. They also report a shorter timeline to parent-child reunification. The average length of time to exit foster care in West Virginia is 17.4 months, lower than the US average of 23.3 months, while West Virginia FTCs achieve reunification in an average of 11.2 months [1].

Additionally, FTCs report that 90% of children who are reunified with their parents after FTC proceedings do not re-enter the foster care system [1]. Analysis from West Virginia’s FTCs estimate they have saved West Virginia $2.6 million in foster care or kinship subsidy payments due to an expedited time to reunification [1].

Family Treatment Court Funding

Although the legislature established FTCs in 2021, there was no funding allocated to support the program. Chief Justice Bunn recently testified that each FTC costs about $100,000 per year to operate. The majority of funding is used to cover staff salaries and benefits, as judges operating a FTC do so on a volunteer basis [1].

Thus far, funding for West Virginia’s FTCs has come from federal grants and opioid settlement funds administered by the West Virginia Office of Drug Control Policy. Due to instability in the federal grant ecosystem and the transition of opioid settlement funds from the Office of Drug Control Policy to the West Virginia First Foundation, FTCs faced a funding gap in August 2025. This lapse in funding was covered by a State Opioid Response grant from the Bureau for Behavioral Health for two months while they sought additional funding opportunities. In September 2025, FTC funding was secured secured for the remainder of the fiscal year from the Public Defender Services’ Impacting Child Abuse and Neglect program, which is funded by Title IV-E.

Similar courts in some other states receive state funding. Ohio, for example, subsidizes their speciality courts, some of which have the same goals as FTCs in West Virginia. Similarly, Maryland’s family recovery courts and Tennessee’s adult recovery courts, which seek to assist adults with substance use disorders, are allocated funding from the legislature [2]. Pennsylvania drug courts, however, are funded through external grants [3].

Funding Options

One option the legislature could seek is to fund FTC programs as requested by the Supreme Court of Appeals, which is estimated to cost about $1.4 million in FY 2027 [1]. This would be similar to Ohio, Maryland, and Tennessee, which provide state funding for these types of courts. If West Virginia were to fund FTCs, they would likely be able to operate in a more financially stable manner. Additionally, FTCs require a significant time commitment from judges, including weekly hearings and meetings, treatment training, and staff training. This may create a barrier to expansion of FTCs. Dedicated funding and resources to help manage case loads may incentivize additional courts to participate in and expand the FTC program throughout the state.

The legislature could alternatively seek to remove FTCs from the Supreme Court of Appeal’s oversight and delegate their oversight to the individual counties in which they serve, as is done in Pennsylvania’s drug court system [3]. This option would enable local counties to either locally fund their own FTC or seek out external grants to support the program. However, this may lead to funding instability, infeasibility for certain counties, or duplication of efforts across the state as counties seek out and apply for grants.

Another policy option the legislature could seek is to regionalize FTCs, with multiple counties feeding into a single FTC. Five of the 13 FTCs in West Virginia already serve multiple counties, such as the FTC for Tyler, Wetzel, and Marshall Counties [1]. Regionalizing FTCs would reduce the total number of FTCs in the state, as multiple counties would be served by the same court, and likely lead to lower operating costs. However, it may also increase accessibility problems, especially for individuals in rural areas, as it would likely increase the distance and time needed to attend their FTC.

Alternatively, the legislature could maintain the status quo of FTCs being funded through external grants. This would be similar to Pennsylvania, where their drug courts are funded through grant funding [3]. There are grant funding sources available, including the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration which awards grants for courts like the FTCs. Relying on grant funding, however, would require the courts to continuously apply for funding on a regular basis. Grant funding is not always guaranteed, and therefore may not be completely stable on a long-term basis, as seen with the potential lapse in funding last summer.

[1] Testimony from the January 2026 Legislative Interim Session.

[2] Based on conversation with the Tennessee Recovery Court Administrator

[3] Based on conversation with representatives from the Carbon County Court of Common Pleas

This Science and Technology Note was prepared by Nathan G. Burns, PhD, West Virginia Science & Technology Policy Fellow on behalf of the West Virginia Science and Technology Policy (WV STeP) Initiative. The WV STeP Initiative provides nonpartisan research and information to members of the West Virginia Legislature. This Note is intended for informational purposes only and does not indicate support or opposition to a particular bill or policy approach. Please contact info@wvstep.org for more information.