Hemorrhagic Diseases in West Virginia Deer Populations

In light of the current EHD outbreak in the Mid-Ohio Valley, this Science & Technology Note covers EHD causes and symptoms, as well as potential methods to decrease disease spread.

Updated October 1, 2025

Research Highlights

Epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) and bluetongue are two viruses that cause hemorrhagic (bleeding) diseases in deer populations.

There is currently an outbreak of EHD in West Virginia, with over 1,500 confirmed cases in 18 counties.

EHD is highly fatal for deer, but poses no health risks to humans.

There is no proven treatment or prevention for EHD or bluetongue in wild deer populations. Some jurisdictions temporarily reduce bag limits to preserve deer populations.

West Virginia hosts over 300,000 resident and non-resident hunters each white-tailed deer season, generating more than $300 million in annual retail sales. In 2024, the recorded deer harvest was 111,646. There are two major hemorrhagic diseases that can decrease deer populations in West Virginia: epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) and bluetongue. Both are viral infections spread by biting insects, and do not pose risk to humans. In light of the current outbreak of EHD in the Mid-Ohio Valley, this S&T Note covers EHD causes and symptoms, as well as potential methods to decrease disease spread.

EHD and Bluetongue Biology

EHD and bluetongue are two different viruses that can infect deer, causing nearly identical disease that can only be distinguished by molecular testing. While EHD is restricted to deer and occasionally cattle, bluetongue can also affect sheep and goats. When deer are found with indications of any hemorrhagic disease, It is important to conduct testing to determine risk for livestock populations. The current outbreak in West Virginia has been confirmed as EHD, which will be the primary focus of this Note.

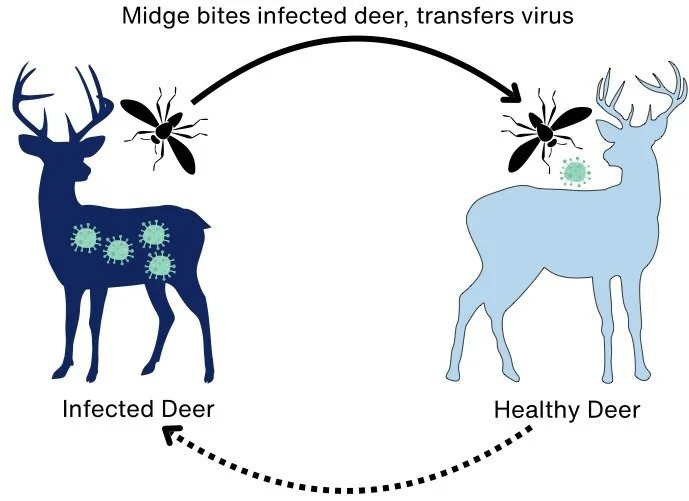

Both EHD and bluetongue are spread by biting midges, also called no-see-ums or gnats. These midges reproduce and live in wet conditions, usually mud holes, and feed on blood from deer and livestock. A single deer can receive over a thousand bites per hour, and it only takes 4 bites from a disease-carrying insect to infect the deer. EHD and bluetongue cannot be spread directly from deer to deer, so these diseases are not associated with increased deer populations. Rather, outbreaks often occur in times of drought, as deer are forced to concentrate around partially dried up water sources that tend to have more mud, and therefore more midges. Outbreaks usually happen in late summer or early fall when midge populations peak, and are quickly stopped after the first frost kills the midges.

EHD and bluetongue infection process. Infected deer (dark blue) are bitten by midges, who serve as vectors for the virus. When the midge bites a healthy deer (light blue), the virus is transferred in the midge’s saliva, infecting a new deer.

Both EHD and bluetongue are hemorrhagic diseases, meaning they cause severe bleeding in infected animals. These viruses disrupt the lining of blood vessels all throughout the body, causing animals to bleed into their lungs, stomach, and intestines. Symptoms usually appear within 2-10 days of infection, appearing as weakness, lethargy, swelling in the head, neck, eyelids, and/or tongue, and bleeding from the mouth and/or nose. Hemorrhagic diseases also cause high fevers, leading the deer to seek out water to cool down. Within 8-36 hours of symptom onset, up to 90% of animals infected with EHD will die, often in or near water sources. Hunters are generally discouraged from harvesting sick-appearing animals because of the risk of chronic wasting disease (CWD) or other potentially dangerous infections. However, meat from EHD-infected animals is safe to eat and handle with standard precautions, and EHD is not known to cause disease in humans.

Current Outbreak

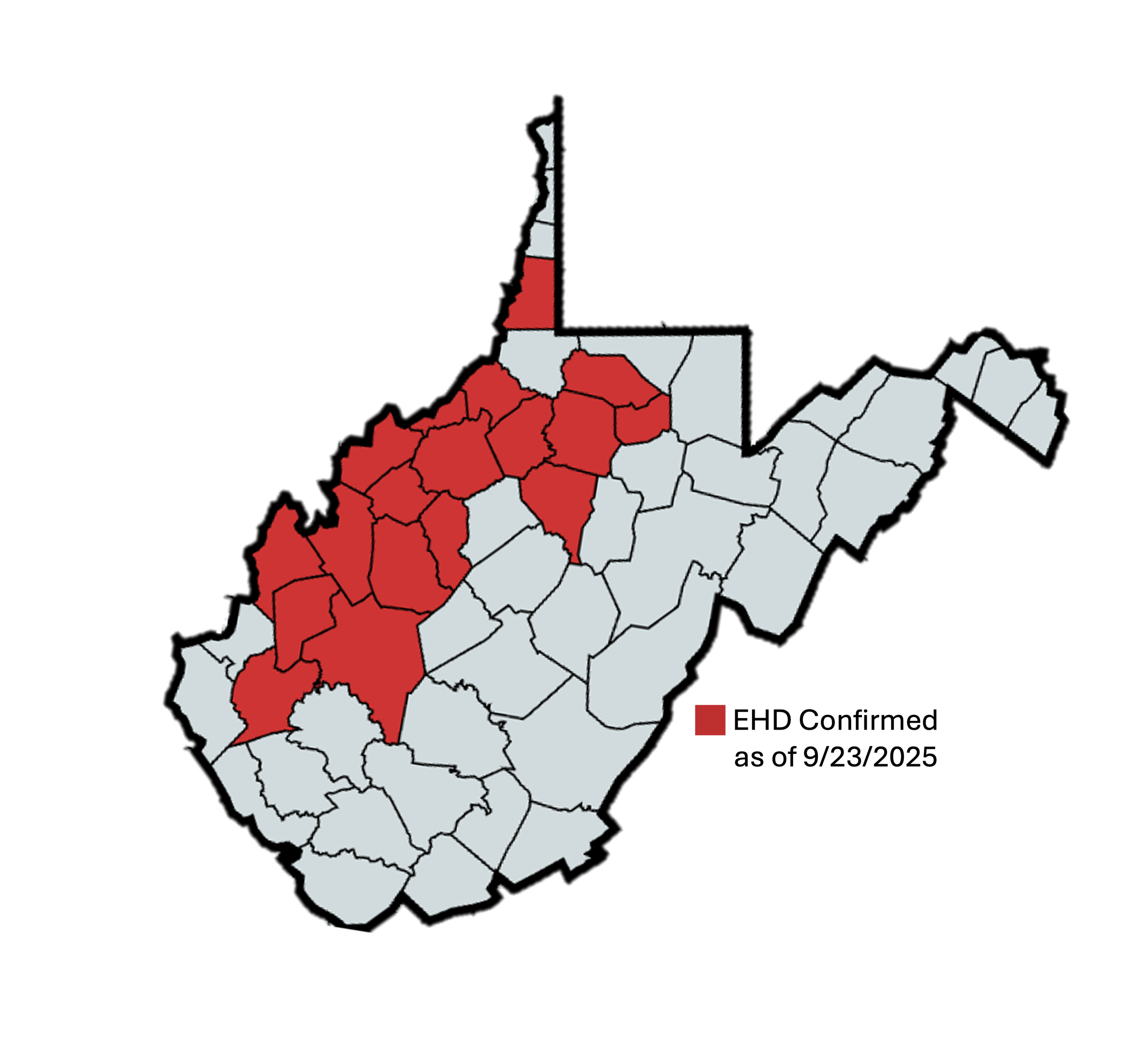

EHD outbreaks are fairly common in West Virginia, with previous notable outbreaks in 1996, 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017, and 2019. The current outbreak in the Mid-Ohio Valley was first reported in Ritchie County in late July and has spread to 18 counties thus far (see map). Cases can be reported to the WV Department of Natural Resources (WVDNR) by individuals who find dead deer on their property or identified through WVDNR surveillance. The WVDNR reported 1,511 confirmed cases of EHD as of September 23, 2025. Ohio has also been impacted by the current outbreak, reporting 8,214 dead or sick deer on the same date. Ohio officials have proposed a reduction in the white-tailed deer bag limit from 3 to 2 for the 2025-2026 deer season in affected counties to allow some preservation of healthy deer and promote re-population. WVDNR officials have stated that they are not considering similar measures but project that harvests will be lower and that deer populations will rebound as seen in previous outbreaks.

Counties with confirmed cases of EHD, as reported by the WVDNR on 9/23/2025

Reducing Hemorrhagic Disease Spread

At least 10% of infected deer will survive EHD, and some southern deer populations have developed immunity to the virus. The fever disrupts hoof growth, allowing for identification of previously infected deer by the grooves in their hooves. Vaccines to the EHD virus are available in Europe and are currently being tested in America, but these are primarily for farmed deer populations and cattle. It would not be feasible to vaccinate wild deer populations, and there are currently no known methods to reduce or contain the spread of EHD or bluetongue in the wild. Some have theorized that providing multiple clean water sources for wild deer populations during droughts may be effective for reducing disease spread, as it prevents concentration around biting midge habitats.

Normal deer hooves (left-AHEIA) compared to the grooved hooves of a deer with previous EHD infection (right-Michigan DNR).

Cattle, sheep, and dogs can be infected with bluetongue, though cattle and dogs are usually asymptomatic. Sheep can get severe bluetongue, and cattle may experience reproductive loss during infection. To reduce transmission of EHD and bluetongue to livestock, the USDA recommends insecticidal pour-ons, ear tags, or back rubs. Additionally, eliminating standing water sources or leaky troughs and pipes that lead to mud holes can limit biting midge populations. If one suspects that an animal has bluetongue, it is important to use single-use needles for administering vaccinations or treatments to prevent spreading the disease between animals.

This Science and Technology Note was prepared by Kensey Bergdorf-Smith, PhD, on behalf of the West Virginia Science and Technology Policy (WV STeP) Initiative. The WV STeP Initiative provides nonpartisan research and information to members of the West Virginia Legislature. This Note is intended for informational purposes only and does not indicate support or opposition to a particular bill or policy approach. Please contact info@wvstep.org for more information.