DNA Use in West Virginia Law Enforcement

This Science and Technology Note discusses when DNA samples may be collected in West Virginia, how those samples are used for law enforcement purposes, and how DNA sample collection laws differ in other states.

Updated September 26, 2025

Research Highlights

DNA is a genetic characteristic unique to each person.

Law enforcement uses DNA technology to assist in their investigations.

West Virginia requires collection of a DNA sample from certain people upon criminal conviction.

Some states have made efforts to expand who must submit a DNA sample to police.

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a genetic characteristic unique to an individual. Law enforcement is sometimes able to use DNA in their investigative process to identify a suspect or link crimes. This Science and Technology Note discusses when DNA samples may be collected in West Virginia, how those samples are used for law enforcement purposes, and how DNA sample collection laws differ in other states.

What is DNA?

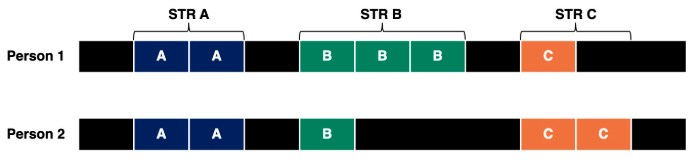

DNA is the molecule that contains a person’s genetic information, the blueprint for who they are. DNA is made up of four building blocks: A, C, T, and G. The order in which these building blocks are found differ between every person, which is what makes us unique. Sometimes, a sequence of 1-6 of these building blocks repeat in a pattern multiple times, called a short tandem repeat (STR). STRs are found throughout the genome and can repeat on average 1-46 times. For example, one region may be CTT-CTT-CTT-CTT, leading to an STR number of 4. Even if one STR is the same length between two individuals, another STR is likely different between them. Multiple STR sequences can be used for identification, similar to how a store barcode works. Portions of two barcodes may be the same, but entire barcodes are unique to each product. This type of analysis is used to help law enforcement solve crimes.

| Person | Number STR A | Number STR B | Number STR C | Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2; 3; 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2; 1; 2 |

Example of 2 people’s STR analysis. Black bars are non-STR DNA and colored bars are STR DNA. The total number of STR repeats and their genetic profile are shown in the table demonstrating that even if two people have the same number of one STR, their copy number for another likely varies.

DNA Sampling in West Virginia

DNA samples began to be collected from people convicted of certain crimes upon the passage of WV SB 252 in 1995. In West Virginia, DNA samples are collected from registered sex offenders and those convicted of a felony or certain misdemeanors including involuntary manslaughter, sexual offenses, and child abuse. Additionally, samples are collected from anyone found not guilty of a qualifying offense by reason of insanity or mental illness, or anyone convicted of a qualifying offense out of state and subsequently transferred to West Virginia. A blood sample is collected and then sent to a laboratory to make a genetic profile of the individual’s STRs. The contributing lab maintains the individual's identity if they should need to be identified in the future, and uploads a de-identified genetic profile to a state-run database.

DNA Databases and Their Use

West Virginia runs a State DNA Index System (SDIS) that contains the genetic profiles from in-state samples. West Virginia profiles 20-24 pre-selected STRs per person, meeting federal guidelines to be included in the National DNA Index System (NDIS). NDIS includes genetic profiles from all 50 states, Washington, DC., Puerto Rico, the US Army Criminal Investigation Laboratory, and those convicted of qualifying federal crimes. The NDIS is managed by a computer system, the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). In total, the NDIS has over 18 million genetic profiles, over 50,000 of which were submitted by West Virginia. There have been privacy concerns surrounding access to these systems and the potential to identify individuals within them; however, CODIS is an offline system requiring an FBI background check to access, and breaches have never occurred. Furthermore, because of the way the profiles are generated, if a breach were to occur, the only information that would be obtained is a series of numbers.

| Lab West Virginia (Originating Lab Identifier) |

|---|

| 06201863 (Specimen ID Number) |

| 13, 11; 38, 20; 12, 7; 19, 19; 5, 12; 49, 16; 14, 25; 42, 31; 19, 13; 28, 27; 13, 15; 8, 9; 31, 30; 17, 10; 25, 25; 29, 31; 23, 26; 19, 15; 2, 3; 9, 8 (20 core loci) |

| NGB (Analyst Identifier) |

Example of a genetic profile on CODIS, based on https://www.dnajusticeproject.org/dna-database

Investigators use DNA found at crime scenes to facilitate solving cases. Genetic profiles are made from the DNA and compared to profiles of individuals already in the state’s SDIS or NDIS using CODIS. Upon finding a match through CODIS, the laboratories involved exchange information and coordinate verifying the match with a new sample from the suspect. While a positive match does not guarantee prosecution, it does help investigators narrow their focus on a suspect or potentially rule out a suspect. Some are concerned about potential mistakes in matching DNA to possible offenders, which has happened in the past. Supporters of DNA technology found that using 20-24 STR markers from a profile yields an extremely low chance of a mistake, around 1 in 1 quintillion.

Samples can still prove useful if they do not immediately match to someone. DNA profiles are kept in the database to await a potential match or to link crimes where the same DNA profile is present. These methods have proven successful in West Virginia, with 1,380 investigations aided by the use of DNA technology in 2023. One example is a sexual assault case that was recently solved after 31 years due to finding a DNA match.

Adding a Profile to the DNA Database

In order to meet federal guidelines to participate in NDIS, genetic profiles must include 20 pre-selected STRs for comparison. State laws vary regarding who is included in their SDIS. Both HB 4627 and SB 556 were introduced in 2024 to expand DNA testing requirements, however they were both voted down. Both bills would have required collecting DNA from someone upon being arrested for a felony crime of violence, a burglary, or a felony offense where the victim was a minor. Proponents of these policies argue that they are an important way to identify potential repeat offenders that have committed previous crimes. Opponents, however, raise concerns about infringing upon a person’s presumption of innocence and racial stereotyping, citing that certain demographics are over-represented in arrests. Other critics worry that DNA collection prior to conviction is an infringement on the 4th amendment, however, the US Supreme Court ruled in 2013 that pre-conviction DNA collection is valid. Should a case be reversed or dismissed, however, records are able to be expunged from the database upon request.

Obtaining DNA in States

Most states have enacted laws similar to what was proposed in HB 4627 and SB 556. 19 states, including Ohio, mandate DNA collection from all felony arrests. 9 states, including Maryland, Virginia, and Tennessee, require collecting DNA from violent felony and burglary arrests. There are 3 states that require DNA collection only from violent felony arrests. Beyond these states, other states have laws requiring DNA collection after convictions take place, however these regulations vary.

Some states, including Pennsylvania and Kentucky, are beginning to implement Rapid DNA technology. This allows police to analyze DNA samples at their booking stations and generate a genetic profile to run through CODIS in less than 2 hours, compared to the 24-72 hours most laboratory tests take. Rapid DNA technology does not require a trained scientist to run the analysis and has been found to be accurate around 85% of the time, which has some worried about its accuracy. These machines also destroy the sample, which may be needed later in the investigation. One concern about implementing this technology is cost, at about $130,000 per machine, not including the chemicals to run samples. West Virginia currently does not utilize this technology, but it could be beneficial for investigations in areas that do not have easy access to a DNA testing site.

This Science and Technology Note was prepared by Nathan G. Burns, PhD, West Virginia Science & Technology Policy Fellow on behalf of the West Virginia Science and Technology Policy (WV STeP) Initiative. The WV STeP Initiative provides nonpartisan research and information to members of the West Virginia Legislature. This Note is intended for informational purposes only and does not indicate support or opposition to a particular bill or policy approach. Please contact info@wvstep.org for more information.